“We’re bringing religion back to our country,” says the one responsible for the images above blending religion, power, and wealth. With efforts to root out supposed “anti-Christian bias” in the government, an overtly Christian worship service being held in the White House, and sermons and prayers being led at the Pentagon, any notion of the separation of church and state seems to have gone by the wayside during the second Trump administration. As this red meat is thrown out to the base, this is cause for celebration for many, particularly those who proudly embrace the label of “Christian Nationalist.” Though much ink has been spilled over what exactly that term means, pastor Voddie Baucham paints the picture when he says:

“If you don’t want Christian nationalism, what other kind of nationalism do you want? Right? Do you want, you know, secular nationalism, Muslim nationalism?…Or if it’s not Christianity that’s the problem, is it nationalism that’s the problem? If we don’t want nationalism, what do we want? Do we want globalism? You know, no thank you, please.”

When presented with this overly simplistic logic, the answer seems obvious. Why not Christian nationalism? While we are at it, why not go ahead and merge church and state into a theocracy? As a Christian, shouldn’t I want the nation in which I live to be more Christian than less Christian? And yet, perhaps there’s more to the story of both America and Christianity. These stories are what I’d like to explore today.

The reason Christian nationalists are acting as if they own the place is because they believe they do. In their thinking, America should be a ‘Christian’ nation because our country was founded as such. But is that true? Certainly, there were Christians fleeing persecution (from other Christians), desiring to practice their religion freely, and finding refuge in a new land back when refugees coming to this place was cool. However, were those who signed the Declaration of Independence all orthodox believers who wanted to set up a ‘Christian’ nation? That’s more complicated. To better answer this question, historical context matters. For centuries in Europe, the church and state operated with significant overlap, and thus, there was a sense in which everything could be deemed ‘Christian.’ However, in the 18th century, Enlightenment thinkers put forward a great many ideas that were decidedly ‘unchristian’ by the standards of confessional orthodoxy. The result of this was often a synthesis of ‘Christian’ and modern philosophy. No better illustration of this exists than Thomas Jefferson literally cutting up a Bible to make a version acceptable to him, particularly its removal of the supernatural (e.g., the virgin birth, the incarnation, miracles, the resurrection, etc.). Those most excited about our nation’s supposed ‘Christian’ founding certainly would not grant Jefferson membership in their churches espousing his views. And yet, he’s a ‘Christian’ to the extent that it furthers an agenda of simplifying/rewriting history.

To be sure, it is entirely appropriate to point out that Christianity influenced the founders of our nation, in that, the Enlightenment came out of Christianity and utilized borrowed capital from it. For instance, the notion that “all men are created equal and are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights” is a Judeo-Christian concept derived from the belief that human beings are made in the image of God — even if Christians themselves have often been woefully deficient in their application of this principle (e.g., slavery, Jim Crow, etc.). However, the preamble to the Declaration of Independence states that this is “self-evident” (i.e., devised from reason and not from revelation/religion), failing to appreciate that what was obvious to them hasn’t been the case throughout most of human history. Using Enlightenment logic that provided common ground with religious beliefs, a government was created that did not have to be grounded formally in a particular faith expression. While a “creator” was acknowledged, this deity did not imply the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, even if a great many claimed that version. The Establishment Clause made it so that people could worship (or not worship in the case of deists, atheists, and the irreligious) as they pleased, but the nation-state was getting out of the business of taking sides. Even if the Enlightenment overpromised on the ability of reason alone in arriving at absolute truth, promoting religious freedom that kept Christians from drowning heretics and fighting wars over ‘god’ has been a positive development.

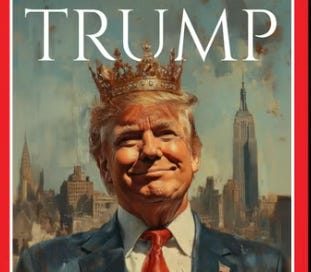

This arrangement worked reasonably well throughout much of American history, primarily because Christianity was almost the only game in town as far as religion was concerned. In fact, Christianity had so much social capital that for many like Jefferson, it would be easier to redefine the faith rather than reject it entirely. As a result, being a ‘Christian’ could mean nothing more than acknowledging the existence of a higher power, subscribing to certain moral positions (even if you don’t keep them yourself), and/or recognizing that the religion is extremely useful in shaping society (often for personal gain). In this sense, Donald Trump is a ‘Christian’ though he doesn’t attend services, knows nothing about the faith, finds no need for forgiveness, and is proudly the opposite of Jesus in every possible way. That’s not to say that there haven’t been a great many throughout American history who sincerely held to the tenets of the faith and put those beliefs into practice. What it does mean is that as ‘Christianity’ became the ‘civil religion,’ an amorphous definition was inevitable that often discarded the particularities of the faith. Since the 4th century, the Christian faith has been summarized from scripture in the words of the Apostles’ and Nicene creeds. This faith once delivered to the saints includes beliefs such as God incarnate coming to this world during the 1st century in the person of Jesus of Nazareth; a Jewish man who died on behalf of sinners, rose from the dead, and empowers his people to follow him by his Holy Spirit. As these are convictions received by faith, they belong not to a nation-state, but to the church Jesus founded, comprised of those who hold to that confession.

It is for that reason that the idea of a ‘Christian’ nation is a theological impossibility. Though many have labeled their countries as such over the last 2,000 years, scripture knows nothing of this. When Jesus sent his followers out to make disciples of all nations, his objective was global in scope, transcending the national. When Jesus said his kingdom was not of this world, he was stating that the nature of his reign was entirely different than those we are accustomed to seeing. When New Testament writers make comparisons to the nation-state of Israel in the Old Testament, the fulfillment is not found in a contemporary nation-state, but in the church, who are referred to repeatedly as “strangers and exiles.” When the New Testament speaks of the place where those who live “by faith” locate their identity, it says the following:

And they acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth. Now those who say such things show that they are seeking a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for He has prepared a city for them. (Hebrews 11:13b-16)

While the hope of heaven has at times led Christians to embrace a sectarian indifference to the affairs of the world, that’s definitely not the temptation of today. The fool’s gold placed before Christians in our day and age is the thought that they can make their version of ‘heaven’ on earth through the political realm. Not unlike the offer made to Jesus in the desert to possess all the kingdoms of the world apart from suffering, this shortcut to “thy kingdom come” is not the way outlined. Scripture teaches that the kingdom comes through proclaiming the good news of a gracious king who rules not by the sword, but rather, through the spirit that changes hearts, lives, cultures, and ultimately the world. To be sure, government still has a role to play in the created order, providing stability and restraining evil (Romans 13). However, categories get confused when governments begin to be labeled as ‘Christian.’ The idea of the separation of church and state not only has been a beneficial concept for our nation’s governance, but for Christians as well, as it differentiates the functions of these two institutions. Of course, the separation of church and state should not imply that Christians cannot have an impact in government. Wherever/whenever Christians find themselves, they are called to be good citizens of the places where they take up residence (Titus 3:1). That citizenship may allow them to exercise more influence in certain political contexts (e.g., a democratic republic) than others (e.g., a one-party totalitarian state). Certainly, they have the potential for more influence now than they did when Paul wrote to respect the governing authorities, even as they were murdering believers. As the religious cannot separate their views from themselves, Christians should have a place in the public square to share their convictions. The question is how they should wield their influence on this side of heaven, especially in contexts where many claim the name of Jesus even as others do not.

Even if it were possible to have a ‘Christian’ nation, what would it look like? Would a ‘Christian’ nation be in keeping with the teachings of Jesus on mercy, forgiveness, peacemaking, meekness, humility, concern for the marginalized/needy, etc.? Similar to the founders, would a ‘Christian’ nation attempt to build consensus on matters where common ground can be found in order to preserve their own freedoms as well as those of others? Or would a ‘Christian’ nation look like passing a legislative bill in the middle of the night that hurts the sick and the poor in order to give tax breaks to the wealthiest people in the world, and then engaging in self-congratulatory prayer as if they are doing the Good Lord’s work? Would it look like making laws for schools that post the Ten Commandments, distribute Trump Bibles that he will profit from, and teaching falsehoods about the 2020 election, all while cutting funding for teachers and lunches for children? Would it look like those in leadership boldly wearing a cross around your neck while spewing propaganda in the White House press room or on a ‘news’ network that paid $787 million for lying to its audience? Would it look like scapegoating immigrants for all the nation’s problems, stereotyping them all as murderers, rapists, drug dealers, even assigning to them sub-human status, and deporting them to third-world nations without due process, thus risking innocent people being lumped in with vile criminals? Because these latter examples of incompetence, corruption, and an unconscionable agenda being associated with Jesus is nothing more than the use of the Lord’s name in vain. Doing so is evidence of a people who have lost their way, have a grossly deficient view of their own faith, and/or are simply using Jesus as a mascot to seize political power in a way that he condemns.

Let’s be clear on what the Christian nationalist agenda is really all about. Over the last 75 years, the nation has changed considerably. Demographics are different, with people from all over the world establishing a home here, which resulted in eight years of an African American (i.e., non-white) president. The religious landscape is different, with other faiths being present bringing their distinct beliefs, along with an increasing amount of people who would claim to be ‘nones’ in terms of their affiliation. Values are different as secularization has changed Americans’ views on social/moral issues, particularly related to sex (sex outside of marriage, abortion, divorce, pornography, homosexuality, etc.) and gender (gender roles, women in the workforce and the impact on family, transgenderism, etc.). As there is no longer cultural homogeneity, Christian nationalists are not content to hold their own views individually and within their faith communities, but rather, seek to make the entire nation reflect what they believe to be true. To be sure, it is undeniable that the changes in our nation present challenges and tensions in our common life. How we can continue to have a national identity in the midst of these shifts is a worthwhile conversation. Would that people of good faith be able to seek to navigate protections of all people’s rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and in doing so, protect their own rights as well. However, the answer of the Christian nationalist is the zero-sum game of just making everything ‘Christian’ again — as if it ever was — in a world where not everyone is the same/agrees. How they go about this presents answers that should be extremely disconcerting to those outside of their tribe. The nationalism within 1930s Europe is instructive here and should not be ignored.

With it being neither ‘Christian’ (i.e., in keeping with the teachings of Jesus), nor ‘nationalist’ (at least by the American values articulated in the nation’s founding documents), Christian nationalism for America should be condemned in the same way as Sharia law should be rejected. This is a betrayal of who we are as a nation and is a compromise of the faith as well. For all the accusations that the left ‘hates America,’ it is this current iteration of the right, fueled by ‘Christians,’ who are brazenly showing contempt for our nation’s values, laws, and even people. The contention that ‘Christians’ (i.e., Republicans in their scheme) must be in charge in order for us to have a safe, prosperous, just, and virtuous nation is being exposed as more and more absurd by the day. While Martin Luther may not have actually said, “I’d rather be ruled by a wise pagan than by a foolish Christian,” I will say it. Give me competence, intelligence, wisdom, integrity, decency, and concern for the common good over the insanity we are living in that is supposedly aligned with Jesus. To be sure, that’s not to say that the other party provides the ‘Christian’ alternative. Given the revelations this week of the cover-up of Biden’s health even as he was running for another 4-year term, the Democrats have egg on their face as well. Perhaps then we’d be better off not declaring either party ‘Christian.’ Given our complicated history, perhaps believers should also resist the urge to call our nation ‘Christian’ as well. Perhaps rather than attempting to make America ‘Christian,’ believers should be more concerned with whether they themselves are being ‘Christian.’ It would be a far more worthwhile endeavor that might actually contribute to the changes they long to see.